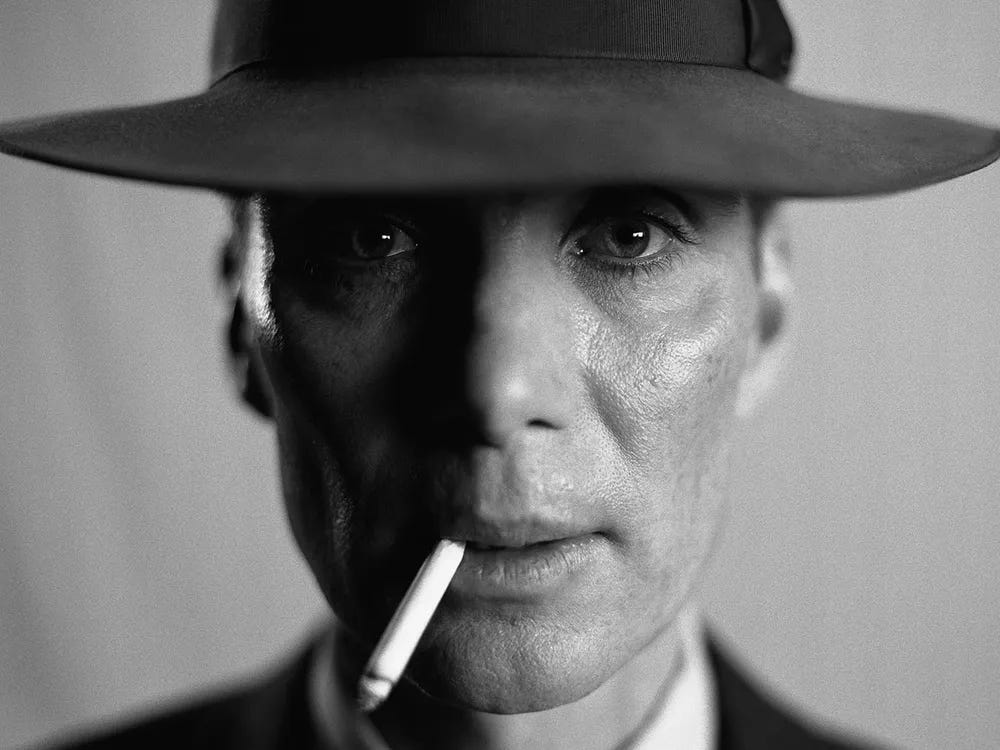

Creating Fear And Genius —The Music Of Oppenheimer

When I watched Oppenheimer for the first time, the music was the first thing I noticed. Ludwig Göransson's score isn't music for the ears – it's a sonic assault on the senses. In the film, traditional biopic tropes are shattered and replaced by science fiction soundscapes and one very a relentless violin.

Music usually guides our emotions –but in Oppenheimer, the music is the emotion.

Göransson’s rise into the mainstream audience began with Black Panther, blending traditional African rhythms, pulsating electronic soundscapes, and sweeping orchestral flourishes that brought Wakanda to life. The Oscar he won wasn’t just recognition; it was a validation that his bold fusion of influences reflected the film’s unique Afrofuturist vision.

His work on the Creed films, and mostly of his movies with Ryan Coogler– swapping out lush orchestration for gritty, hip-hop-inspired beats – showed us he has a chameleon-like ability to adapt his sound to the emotional core of a project.

But Tenet marked a turning point. If you’re not very familiar with Göransson’s dynamic range, you might’ve mistaken the score’s bombastic, brass-heavy soundscapes for the work of Hans Zimmer. But it wasn’t a mere imitation, though. It was strategic, a calculated risk to step into the territory of a veteran composer and impress the notoriously meticulous Christopher Nolan, which he did well enough to get a shot in Oppenheimer. But that collaboration announced Göransson’s arrival as a force to be reckoned with.

With Oppenheimer, though, the composer stepped away from his previous works. Biopics usually rely on sweeping piano melodies to highlight emotional beats, manipulating audiences with something I’d like to call “familiar cues.” Instead, The Swedish International opted for a chilling, science fiction-infused soundscape. And a single, insistent violin motif, evolving and morphing throughout the film, became the embodiment of Oppenheimer’s own internal struggles, which were coincidentally Nolan’s most consistent themes: time, destruction, and the inescapable weight of his creation.

Göransson said, “and he [Nolan] told me like ‘I don’t have a lot of things to tell you what I want to the music to sound like, but I have one idea; and that is to use the violin to portray Oppenheimer.’”

The film is like this shattered timeline. “Fusion” and “Fission” are the pieces stuck in black and white, the other careening towards this insane past. A study in both the subjective and the objective. And Nolan, being the timeline-bending genius he is, uses the music to guide us through the chaos, saying, “Don’t just watch this, listen to it.”

“Fission” is where it all starts. The music there has this slow, haunting feeling – it almost makes you want to curl up and cry a little.

But “Fusion " is a different beast; it’s probably where the bulk of the movie happens and has this intense, have-to-move-NOW energy. But even with all the changes between the two realities, there’s this violin that keeps rising and falling in the background, almost like the film’s own weird heartbeat, marking the way time loops and twists on itself but, more importantly, captures Oppenheimer’s internal struggles.

“I realised that what I really needed to encapture first is the emotional core of Oppenheimer's journey…there was something about this kind of feeling of loneliness that I got from the script,” the composer noted.

The real mind-bending part is what Göransson does with the ordinary, almost like ticking. He takes that normal, everyday thing and stretches it, warping it until it’s not about minutes passing anymore. It’s about how time gets messed up, a perfect fit for a film where physics goes haywire and the atomic bomb casts this long, terrifying shadow.

Scrap metal clangs, pianos that sound like they’re being tortured – it’s like walking through the world’s weirdest sound factory.

But the ticking was woven into everything. One minute it feels like a clock; the next, it’s like a Geiger counter freaking out, and then it’s like a countdown to the apocalypse, all represented with subtle rises and falls in the violin.

Even with the sounds going all over the place, the ticking is still there, like this constant reminder that something huge is brewing and time might not be on our side. It plays into that whole question the film keeps asking – can we change what’s meant to happen, or is our fate already ticking down?

This composer had a knack for getting under your skin. Like pure anxiety buzzing in your ears. With notes that sounded like a mind fraying at the edges, barely holding onto sanity. It was like he took all of Oppenheimer's genius and deepest fears and toured them straight into the music.

“Depending on the performance, You can have this beautiful, somber romantic note in vibrato… You can switch it into something horrific, and you can go between those emotions very, very quickly,” Göransson said, highlighting how important the violin was during the whole creative process.

“That was something that resonated with the script and with the nature of Oppenheimer and his complex character.”

“Can You Hear the Music” and “American Prometheus” are some of the complex tracks in the score. They start slow, those violins building tension with every strained note. But it’s also where we first hear the distorted synth Göransson calls “saw glide” that actually becomes the haunting background element you kind of feel all through the movie and describes it as “introducing a dangerous element” into the score.

You get these hints of melody that twist and turn, never quite settling into something comfortable. A fragile counterpoint flickers in and out, promising a moment of peace, but then – whoosh! – it all explodes into this relentless, chaotic climax. And the thing is, that climax never really ends. It just keeps spiraling upwards, this terrifying echo of the atom’s infinite destructive potential.

But the really brilliant part, the part that makes your hair stand on end, is how Göransson doesn’t just play with notes and rhythms. He builds this whole sound world that drags you into the heart of the science. He went on to say;

“After I saw these visual effects, the molecules swirling around, I felt like I needed to write some music that also had the math and science in it.”

The shattering of glass hints at how matter breaks down on a subatomic level, those fiery crackles become chain reactions, and a vibrating sphere, stretched too tight, shrieks of nuclear fission. This music doesn’t just explain quantum physics and the horrors of the bomb – it forces you to feel it in your bones, to confront the awe and terror of it all.